LA, Los Angeles The GPS gadgets are distributed to the homeless patients so that they can monitor their progress. Glass pipes that are used to smoke meth, crack, or fentanyl are included in the many street kits that they sell. They keep credit cards issued by the company on hand in the event that a patient need immediate assistance, such as food or drink, or an Uber ride to the doctor.

A new business model is gaining traction in towns all around the state of California, and these medical professionals, nurses, and social workers are spreading out across the streets of Los Angeles to serve homeless people with health care and social assistance. They are the foot soldiers of this new business model.

For the purpose of delivering medicine to homeless people wherever they are and making money in the process, their method is to establish trust with those individuals.

“The largest population of homeless people in this country is here in Southern California,” said Sachin Jain, a former health official in the Obama administration who is now the CEO of SCAN Group. SCAN Group is the company that manages a Medicare Advantage insurance plan that covers approximately 300,000 people in the states of California, Arizona, Nevada, Texas, and New Mexico.

According to him, the demographic of people who are suffering homelessness that is expanding at the quickest rate is actually older seniors. The statement that I made was, “We have to do something about this.”

Three years ago, Jain’s company founded Healthcare in Action, a medical organization. Its main mission is to provide medical assistance to homeless individuals by sending practitioners out into the streets of California. The company has experienced significant expansion, establishing businesses in seventeen different areas, some of which include Long Beach, West Hollywood, and San Bernardino County.

Healthcare in Action has provided medical assistance to over 6,700 homeless patients and has treated approximately 77,000 diagnoses, ranging from schizophrenia to diabetes, since it was first established. It has provided around 300 individuals with either permanent or temporary accommodation.

Most of the nation’s street medicine is done as a volunteer project, meant to serve a demanding patient population neglected by conventional care, its supporters claim. Homeless people live nomadic, chaotic lifestyles and suffer disproportionately from mental illness, addiction, and chronic disease; they also often lack health insurance or use it sparingly.

Designing a business around looking after them runs the danger, health economists and insurance executives advise.

“It’s really innovative and entrepreneurial to take all this energy and grit to try and improve things for a population that is too often ignored,” said Mark Duggan, a Stanford University economics professor focused on Medicaid policy and homelessness. “In health care, financial incentives count greatly. Everything is fine.

About thirty percent of the country’s total, or an estimated 181,000 people, were homeless in California in 2023. More than two-thirds of California’s total, the number of people living outside, grew by 6.9% over last year.

Despite allocating unheard-of public funds, the state’s officials, notably Democratic Governor Gavin Newsom, have struggled to create inroads against the growing political crisis and public health threat.

“We have a huge problem on our hands, and we have a lot of health plans and municipalities saying, ‘We need you,’ Jain said.”

On the Streets

In Long Beach, on a foggy morning in April, Daniel Speller drove his mobile medical van through the crowds of tents and tarps that were occupying residential streets. He was looking for a couple of patients who were homeless. Speller, who works as a physician assistant for Healthcare in Action, expressed his concern regarding the severely infected wounds that the individuals had gotten on their limbs as a result of their usage of the illegal substance xylazine, which is an animal tranquilizer that is frequently combined with fentanyl.

Wounds like these can be found everywhere. “It’s a terrible situation,” Speller stated. Depending on the severity of the infection, it may be necessary to amputate a toe, foot, or arm.

While removing denim jeans from the swelling leg of Robert Smith, 66, Speller remarked, “Man, this one is still so deep.” Smith was one of the patients.

After cleaning and wrapping Smith’s leg, Speller inquired as to whether or not he required any other assistance. “I got rid of my food stamps,” Smith said in response.

Within the hour, Speller’s team of social workers and nurses had called an Uber to drive Smith to a state office, where he was given a new CalFresh card. Smith was the recipient of the new card.

After that, Speller steered his medical van onto a side street that was lined with further tents and cars that had been converted into shelters. Nick Destry Anderson, who was 46 years old at the time, was suffering from a severe wound and was sleeping on the pavement.

I was so terrified. During the time that Speller was spraying antibiotic mist on Anderson’s leg, Anderson grimaced and remarked, “I thought I was going to lose my leg before getting to meet them.” They were the ones who prevented my death.

After receiving a report that Anderson was experiencing dizziness, Speller requested that another member of the team use the company credit card to purchase a cheeseburger and a Sprite for Anderson.

A significant number of people who are homeless choose to remain on the streets because they are so deeply entangled in mental health problems or addiction that they do not care much about going to the doctor or taking their medication. The severity of chronic diseases increases. When wounds become infected. Individuals either die from treatable diseases or overdose on drugs.

Street medicine includes the application of bandages to infected wounds, the administration of antipsychotic injections, and the treatment of existing chronic conditions. Providers on the street frequently distribute drug paraphernalia, including clean needles and glass pipes, in an effort to decrease the amount of sharing that occurs and to prevent infections. These workers, maybe more crucially, establish confidence in the community.

Getting homeless patients established with primary care doctors and nurses, who visit them on the streets, in parks, or wherever they happen to be, might reduce frequent and expensive trips to the emergency room and hospitalizations, which could potentially save money for insurers and taxpayers, according to Jain’s argument. According to him, the objective of Healthcare in Action is to ensure that patients are healthy enough to lead stable and independent lives, despite the fact that housing and shelter are in short supply.

It is, however, much simpler to say than to do. Isabelle Peng, the clinical coordinator for Healthcare in Action, discovered Lisa Vernon, a homeless lady, slumped over in her wheelchair at a crowded bus stop in West Hollywood during the week of April. According to Peng and her colleague David Wong, Vernon is a frequent patient at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, which is located nearby.

While Peng and Wong were attempting to inspect her swollen leg, Vernon yelled at them and refused to participate in the examination. Not even antibiotics are going to be able to save my life! While a mouse was frantically searching for the potato chip shrapnel that was at her feet, Vernon exclaimed.

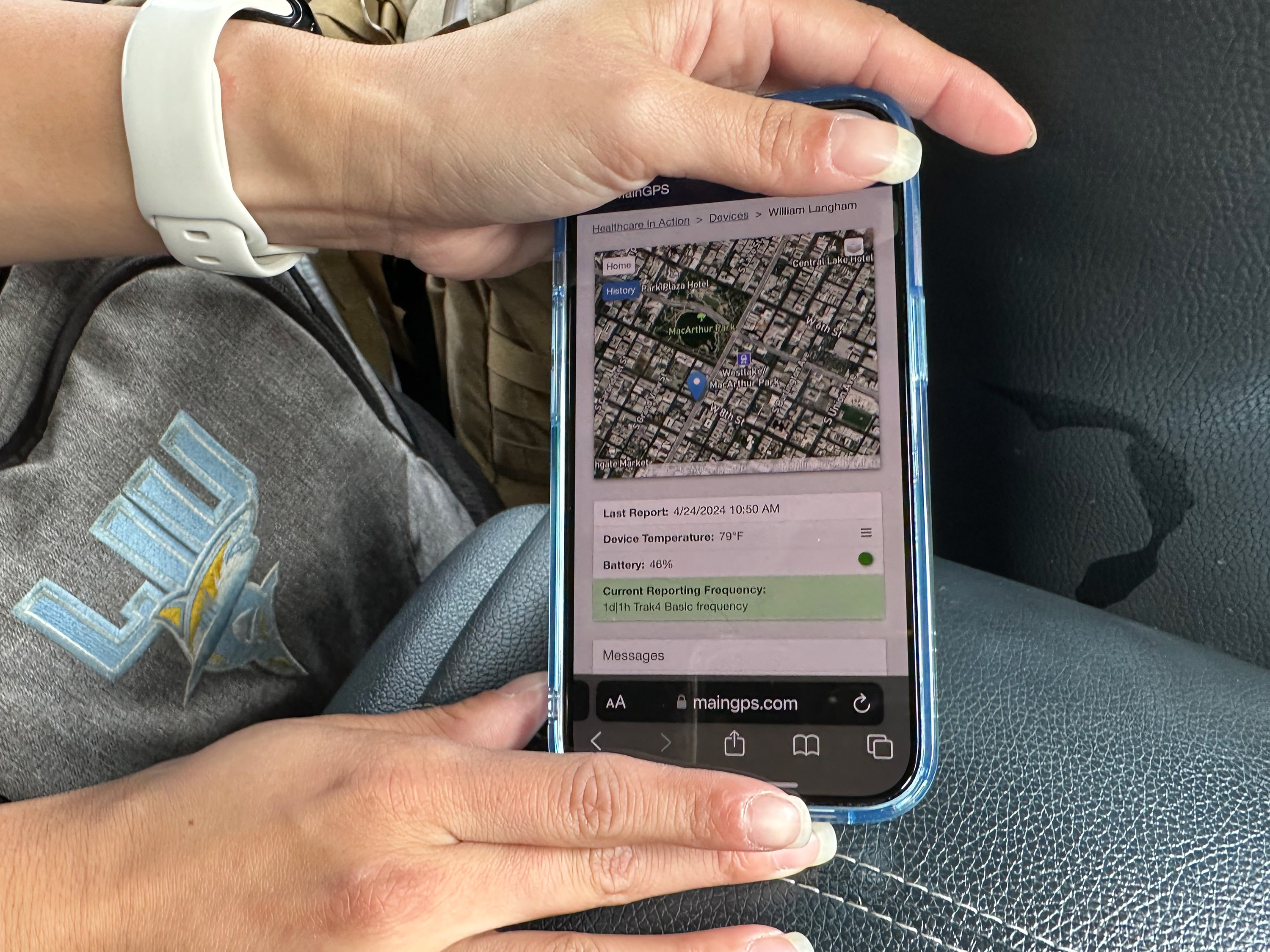

Next, they moved on to their next subject, a man whom they were monitoring with a global positioning system (GPS) device that they sometimes attach to the effects of homeless people. The use of the devices is entirely optional. When compared to telephones, they are more effective due to the fact that they are less likely to be removed by law enforcement during encampment sweeps or stolen by thieves.

As a result of the fact that our patients move around quite a bit, this makes it easier for us to locate them when we need to provide them with medication or provide follow-up treatment, as Wong explained. Our relationship with these patients has already been established, and they have expressed a desire for us to visit them.

Growing Revenue

- Street medicine teams are in demand, largely because of growing public frustration with homelessness. The city of West Hollywood, for instance, awarded Healthcare in Action a three-year contract that pays $47,000 a month. The nonprofit can also bill Medi-Cal, California’s Medicaid program, which covers low-income people, for its services.

- Mari Cantwell, a health care consultant who served as California’s Medicaid director from 2015 until early 2020, said Medicaid reimbursements alone aren’t enough to fund street medicine providers. To remain viable, she said, they need to take creative financial steps, like Healthcare in Action has.

- “Medicaid is never going to pay high margins, so you have to think about how to sustain things,” she said.

- Healthcare in Action brought in about $2 million in revenue in its first year, $6 million in 2022, and $15.4 million in 2023, according to Michael Plumb, SCAN Group’s chief financial officer.

- Healthcare in Action and SCAN’s Medicare Advantage insurance plan generate revenue by serving homeless patients in multiple ways:

- Both are tapping into billions of dollars in Medicaid money that states and the federal government are spending to treat homeless people in the field and to provide new social services like housing and food assistance.

- According to the state, Healthcare in Action has been able to hire social workers, doctors, and clinicians for street medicine teams as a result of receiving $3.8 million from Newsom’s $12 billion Medicaid plan called CalAIM. This funding has enabled the organization to hire these individuals.

- Furthermore, it enters into arrangements with health insurers, such as L.A. Care and Molina Healthcare in Southern California, in order to locate housing for patients who are homeless, negotiate with landlords, and offer financial assistance, such as covering security deposits.

- Some hospitals and insurers, such as CalOptima in Orange County and Healthcare in Action’s own Medicare Advantage plan, SCAN Health Plan, contribute to the organization’s charity drive by collecting donations.

- For the purpose of providing treatment and services, Healthcare in Action collaborates with medical facilities and municipalities. In the year 2022, it began providing medical attention to patients who were waiting outside of the hospital under a partnership with Cedars-Sinai.

- Additionally, it enrolls homeless patients who are qualified for enrollment in the SCAN Health Plan. This is due to the fact that many elderly people with modest incomes are eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare coverage. In 2023, the plan generated revenue of $4.9 billion, which was an increase from the $3.5 billion it generated in 2021.

“There has been a remarkable market fit, unfortunately,” Jain said. “It’s impossible to navigate the streets of Los Angeles, regardless of your socioeconomic status, without encountering this issue.”

Jim Withers, the individual who first introduced the concept of “street medicine” many years ago and dedicates himself to caring for homeless individuals in Pittsburgh, expressed his appreciation for the increased number of providers due to the overwhelming demand. However, he advised against a model driven by financial incentives.

“I have concerns about the increasing influence of corporations in street medicine and the intrusion of capitalism into the work we have been doing, which has primarily been driven by our commitment to social justice and operating outside of the conventional healthcare system,” he expressed. However, it is important for everyone to learn how to coexist peacefully on the streets.