LOS ANGELES – After a particularly grueling shift of lifting heavy boxes in an Amazon warehouse in New York State, Keith Williams’ hands and wrist stopped working – when he woke up the next day, he could barely grasp a milk jug.

Williams said the February last year injury occurred due to the breakneck pace of work that Amazon enforced at its facility, which the company had implemented by measuring his productivity precisely and constantly urging him to work faster.

“If you don’t scan a box fast enough, you end up on a list,” he said, adding, “It was just too much for my body to endure.” William is working to unionise his warehouse with the Teamsters.

Such injuries animated lawmakers in Washington, D.C. to propose the Warehouse Worker Protection Act, a broad and potentially transformative federal bill that, among other things, would strictly regulate productivity targets in the warehousing industry.

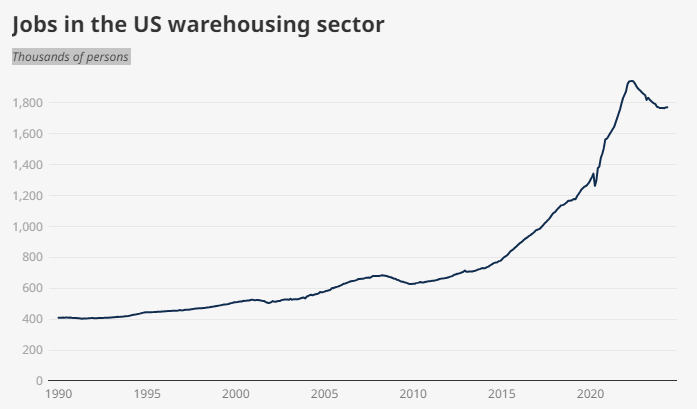

It’s one of the fastest-growing industries in the U.S. today, employing nearly 2 million Americans.

But companies are “treating workers like they are disposable,” Massachusetts Senator Ed Markey, the bill’s sponsor, told Context.

They deserve steadier and more dependable standards of quality that safeguard their basic safety, dignity, and respect in work performance, he added.

Markey’s bill, which mirrors more than a dozen similar proposals in U.S. states, would require companies to inform employees of their quota or productivity targets. If workers don’t know what the expected production levels are from them, they might feel pressured into working harder and faster.

The bill further bars employers from holding workers to standards that regulators determine constitute a risk to their safety.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce business association, though, has come out against the bill, calling it too onerous a burden on the warehouse sector.

“That’s just intrusive micromanagement by the federal government,” said Marc Freedman, workplace policy vice president at the chamber, in an interview with Context.

He said warehouses already do what they can to protect their workers, and that it is improper for regulators to prescribe to companies how they should monitor and enforce productivity.

A nearly $6 million fine against e-commerce giant Amazon in June was the largest ever under the state’s version of the law, with California regulators citing the company for failing to disclose productivity targets as required by law.

Similar fines have been levelled against discount retailer Dollar General, and food distributor Sysco.

Amazon disputes the notion that it has quotas in its warehouses and says it is appealing the fine.

“Nothing is more important than our employees’ health and safety,” spokesperson Maureen Lynch Vogel said in a statement.

Amazon said only an extremely small fraction of workers were let go due to performance issues, and that workers could freely discuss expectations with managers.

Warehouse boom

Fuelled by an explosion of ecommerce and delivery, the number of jobs in the warehousing sector has almost tripled over the last decade to nearly 2 million, according to data published by the Federal Reserve.

It is dangerous work, however, with an injury rate more than double that of an average workplace.

Advancements in monitoring technology and analytics give companies more tools to push workers to the edge of what is safe, said Jordan Barab, a former senior official with the federalOccupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA.

“With productivity algorithms you find all types of sophisticated ways to get workers to work faster, even if it’s less safe,” he said to Context.

Among these was California’s warehouse law, AB 701, which went into effect in 2021, a measure requiring warehouses to disclose performance targets directly to workers, and allowing regulators to intervene if those targets were unsafe.

“There’s no pause button. There’s no stopping. You have to keep making the rate,” said Nanette Plascencia, a worker and labor organiser at the ONT8 warehouse in Moreno Valley, one of the facilities cited by California regulators.

“And if you slow down because you’re hurting badly, it’s still ultimately going to be your fault.”

It had reduced injury rates, and all workers, in addition, could check their performance at kiosks within the facilities, said Amazon.

It said the nature of work in its warehouses was being mischaracterised.

“This isn’t how performance expectations work at Amazon,” said Lynch Vogel. “Our approach insures everybody’s on a level playing field and their performance evaluation’s insulated from things outside of employees’ control — like changes in the business, inventory, freight mix, or seasonal impacts.”.

With fierce backing from union groups trying to unionise Amazon warehouses across the country, variations of AB 701 have since been taken up by other states, and similar laws have been passed in New York, Washington State, Oregon, and Minnesota.

The quota regulations are necessary for workers’ safety, according to Representative Emma Greenman of Minnesota, who helped spearhead the law.

“One of the things that was getting people hurt was not knowing and speeding up to this opaque – felt pretty Orwellian – idea that, I don’t know if I’m going to be punished because I don’t really know what standard I’m being held to until I’ve not done it and I will be disciplined or fired,” she told Context.

In June, Minnesota’s Department of Labor and Industry fined Amazon over the citations for the failure to provide a written copy of a quota to workers in the state and failing to protect them from ergonomics hazards. Amazon has contested the citations.

“We follow all state and federal laws and don’t have fixed quotas,” said Lynch Vogel.

“Despite sharing this information and more with Minnesota OSHA during their investigation, they’ve chosen to issue a citation which reflects a lack of understanding of how we measure performance,” she said.

Spotlight on Amazon

Labour groups and workplace safety advocates have zeroed in on Amazon, which operates most of the country’s biggest facilities and is by far the largest player in the industry.

The California Labor Commissioner’s office stated it made a list of warehouses that had more than 1.5 times the average injury rate for the sector, and conducted nearly 100 site visits.

“Amazon has been milking new tech and pioneering new management tactics,” said Irene Tung, a researcher at nonprofit National Employment Law Project.

A report co-authored by Tung and published in May said Amazon accounted for 79% of employment in large U.S. warehouses that employ more than 1,000 workers, but 86% of all injuries in those workplaces.

Amazon said in a statement that NELP was “misconstruing data, or intentionally leaving out important context in order to fit a false narrative”.

Last year, OSHA handed out $150,0000 in citations for safety violations at several of Amazon’s warehouses nationwide – which Amazon has appealed.

Amazon also appealed this year a decision by the French data protection authority CNIL to slap the company with a 32 million euro ($35 million) fine for putting in place a system to monitor workers’ activities and productivity. CNIL called the system “excessively intrusive”.

The company has released its own data that it says shows steady improvements in injury rates year-on-year.

He also pointed to a company blog post listing a number of ways Amazon has attempted to deploy technology—from ergonomically designed workstations to robotic assistance—that he said eases the load on workers.

The company did not directly answer questions about its stance on the WWPA, which would set up a national “Quota Task Force” to help with enforcement and training.

Freedman, of the Chamber of Commerce, argued that such laws would end up increasing the cost of warehousing for consumers. “It would create new costs, and those costs could be passed down to everybody,” he said.

($1 = 0.9264 euros)